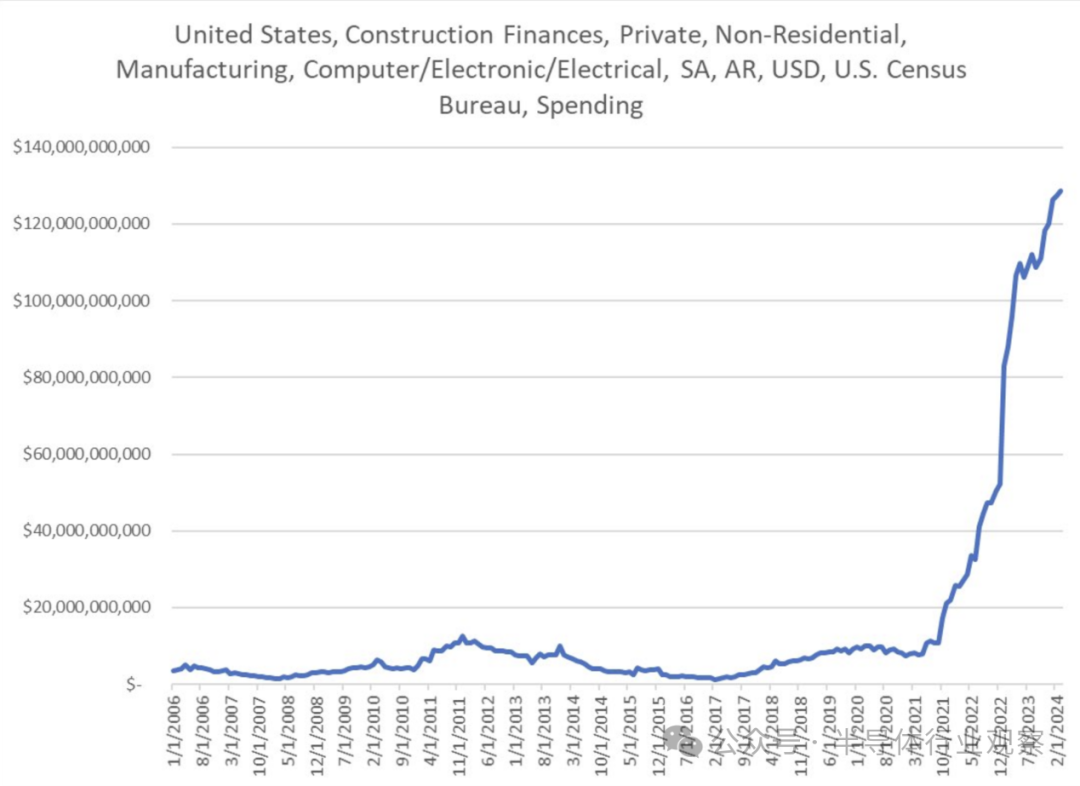

The Biden administration's Chip and Information Systems Act is injecting funds into the chip manufacturing industry at a historic pace. According to a recent report from the US Census Bureau, the growth in construction funds for the computer and electrical manufacturing industry is so rapid that the US government will increase funding for the industry by the same amount as in the previous 27 years in 2024 alone.

A recent tweet by Martin Chorzempa, a senior researcher at the Peterson Institute, has drawn attention to this surge and highlighted the rapid growth in spending over the past few years. Please note that the displayed numbers represent the actual construction expenditure figures, not just the budgeted prices.

The construction growth began in 2021, but its explosive growth was thanks to significant funding support from the Chip and Science Act, a $280 billion spending plan passed by the Biden administration in 2022. The bill aims to help boost the US semiconductor industry, which actually accounts for 0% of all advanced process chips manufactured globally. Companies including Intel, Samsung, and Micron have all received billions of dollars in funding to build new manufacturing plants in the United States. Domestic research and development is also the main focus of this financing plan.

The construction funds have had a significant impact on the expected chip production in the United States. A recent study by the Semiconductor Industry Association found that by 2032, domestic chip manufacturing capacity in the United States will triple, and it is expected to produce 30% of the world's cutting-edge chips by the same year. This expectation even exceeded the government's exaggerated goals; US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo boldly announced her goal of owning 20% of the world's cutting-edge chips in February alone, and now it is expected that this goal will far exceed.

The construction of most new factories is still ongoing, such as Intel's new campus in Ohio, which occupies roads with a load of 900000 pounds. Intel's Ohio factory and many similar factories will become the main participants in the chip manufacturing field, and cutting-edge chip process development is expected to eventually settle in the United States, while larger and simpler processes typically carried out at American wafer factories will take them to the next level.

Despite the enormous cost, most domestic wafer fabs in the United States have experienced significant delays in construction: Samsung, TSMC, and Intel have all been delayed by one year or more from their original plans. This is mainly attributed to inadequate regulation, which has also made the United States one of the slowest countries in the world in chip manufacturing and construction.

Can the United States become a major semiconductor winner?

After 20 months, it is time to re-examine the core of the Biden administration's economic policy: the Chip and Science Act and its $39 billion subsidy to stimulate the construction and equipment of US chip and semiconductor factories. Undoubtedly, this legislation and its funding are based on political and economic risk control, as well as an attempt to revive backward domestic production.

It is worth noting that TSMC, headquartered in Taiwan, produces 90% of the most advanced chips and 100% of ultra advanced GPU chips for artificial intelligence. Chris Miller, a professor of international history at Tufts University, said at a recent conference at the Aspen Institute, "No other industry is so important to the entire economy, and it is so concentrated in a country."

The Biden administration currently has 150 Ministry of Commerce staff responsible for the project. They provided $8.5 billion in direct funding to Intel, which is the largest amount of funding provided to an industry company to date, to support $100 billion worth of construction in Arizona, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon. TSMC, as well as semiconductor manufacturers Global Foundries and Samsung, have also received project funding.

Although the government encourages project labor agreements to promote union contracting, the funding notice from the Ministry of Commerce does not require chip manufacturers to use project labor agreements. Miller insisted that, like all federal grants, wages under the Davis Bacon Act were necessary, but labor only accounted for a "moderate" portion of overall construction costs.

According to Michael Schmidt, the Chips project manager for the department, federal subsidies have brought in $300 billion in promised investments for private enterprises so far. He claimed that when visiting some expanding facilities, he would see "10000 construction workers" coming and going, and "50 cranes" working.

Although these massive funds will enhance the United States' self-reliance in an increasingly digital world, they cannot make it independent in chip manufacturing. Boston Consulting Group predicts that even by 2032, the number of various types of chips produced by newly built and expanded factories in the United States will triple, and the United States' global share will reach 14%, up from 12% in 2020. According to different estimates, the share of the United States in cutting-edge chip production should increase to between 20% and 28%. Competitors in Europe and Asia are also expanding production capacity.

In this crucial industry, various arguments against interference in the global free market are of little significance, especially when considering the potential impact of war or earthquakes. Without the CHIPS Act, the production share of the United States could potentially decline to 8% by 2032- and this should never happen.